History of Sloppy Joe’s

Late 1930s/early 1940s

The History of Sloppy Joe’s

It was dark the night Sloppy Joe’s Bar disappeared. It was in the middle of the Great Depression and many things were disappearing in the Florida Keys around that time; for example, money and jobs. Key West, itself, was teetering on the brink of complete financial disaster, and the dark nights somehow seemed darker than ever. Still, even that did not explain how a full-sized saloon, like Sloppy Joe’s Bar, could up and disappear in the middle of the night.

The last in a long chain of islands dangling off the southern tip of Florida, and first named Cayo Hueso (Bone Island), it was renamed Key West in 1822. Key West has attracted a blend of characters, cultures, and customs ever since. Cuban cigar makers, New England shipbuilders, Bahamian salvagers, lofty southern merchants, and even a few wandering pirates all left their mark on the island that lies 157 miles from Miami but just 90 miles from Havana.

Key West’s easy-going tropical atmosphere has enchanted well-known artists and writers, escapees from the real world, and an ever-growing number of visitors. It’s an island of glorious floral abundance and engaging lunacy of character. Key West’s rowdiness and exceptional fishing entranced Ernest Hemingway for more than a decade. And the appeal prompted former president Harry Truman to say, “I’ve a notion to move the White House to Key West and just stay.”

During the Depression, however, the island’s appeal was almost overshadowed by financial hardship. Once the richest city in the United States, it declared bankruptcy; and although the government suggested relocating the entire population to a more fortunate area, the hardy islanders vowed they would stay and survive somehow. Somehow, they did.

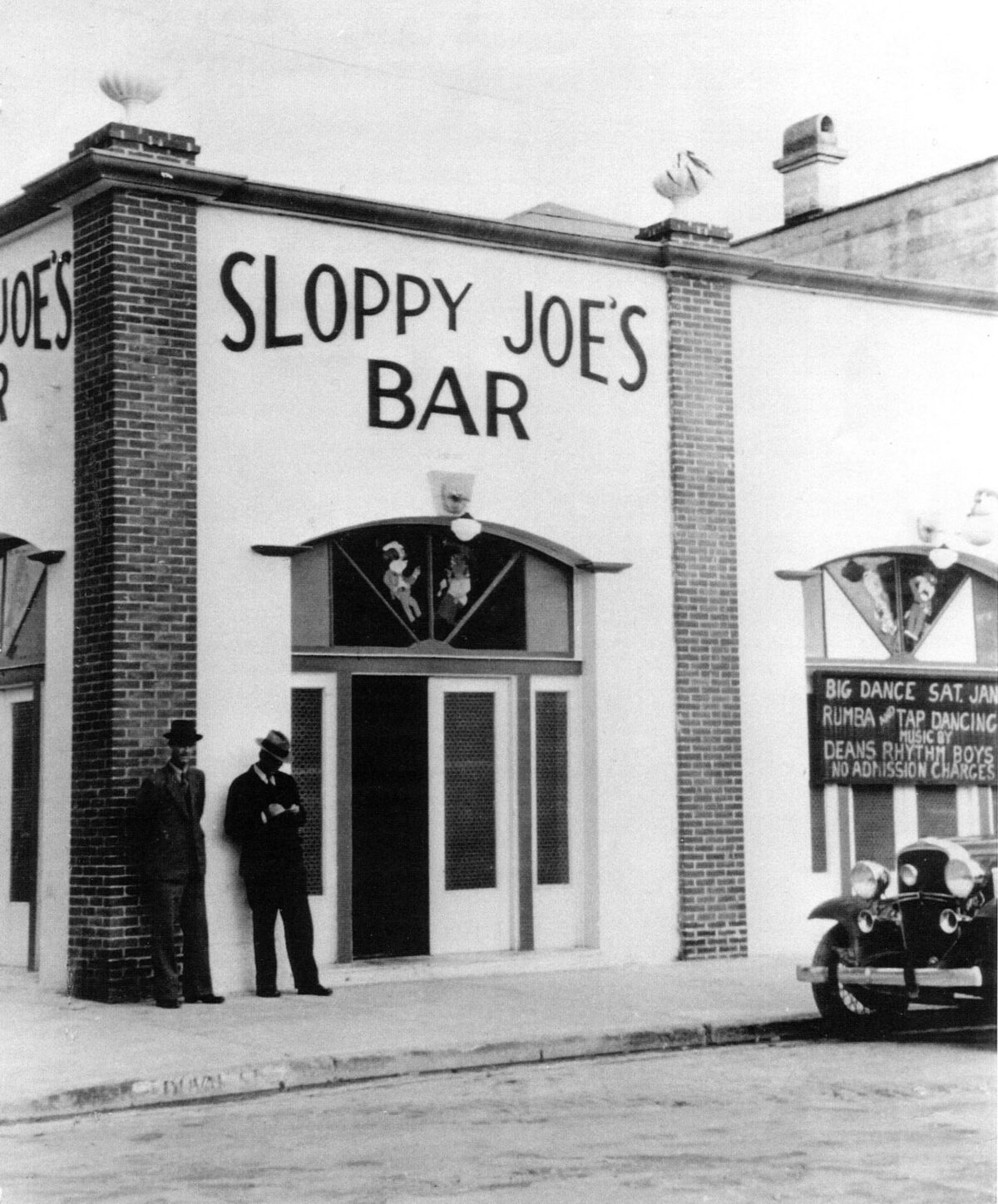

Florida Keys Public Library – Sloppy Joes Bar and Owl Taxi Company at 201 Duval Street. From the DeWolfe and Wood Collection in the Otto Hirzel Scrapbook. 1940s

A Key West Tradition Begins

The official beginning of Sloppy Joe’s Bar, the famous and infamous Key West Saloon beloved by Ernest Hemingway, was smack in the middle of the Depression, December 5, 1933, the day Prohibition was repealed. But the bar was destined to go through two name changes and a sudden change of location before it would become today’s Sloppy Joe’s Bar seen by millions of visitors to Florida’s southernmost outpost.

In Key West, a bastion of free-thinkers even in the thirties, Prohibition was looked on as an amusing exercise dreamed up by the government. Joe Russell was just one of the enterprising individuals who operated illegal speakeasies; his being a raunchy hole in the wall on Front Street near the harbor. Even Hemingway slipped over to Russell’s on occasion to buy illicit bottles of scotch.

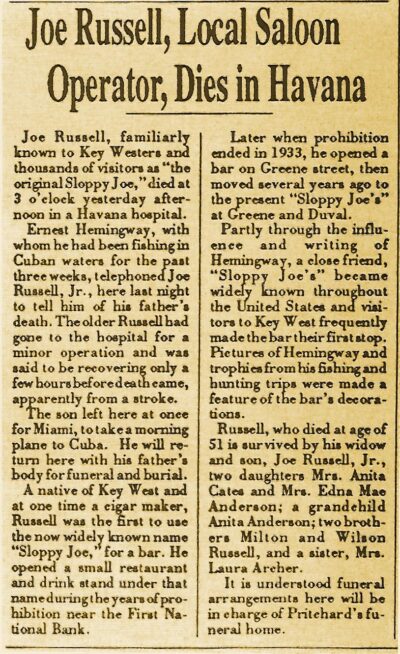

Joe Russell was a Conch born and raised in Key West. Conch is the name given to Key West natives; a name that derived from that of the tough, tasty mollusk found in the waters surrounding Key West. Russell a charter boat captain who ran a 32-foot cruiser called the Anita, eventually became Ernest Hemingway’s boat pilot, and was the author’s fishing companion for over twelve years. In his company, Hemingway once caught and astonishing 54 marlins in 115 days.

Joe knew the Cuban waters like he knew his own skin and not just for their fishing potential. He was one of the daring rumrunners in the Florida Keys, thriving on the rush that came from making a successful run across the night waters; playing games with the Federal agents; dodging in and out of the tiny bays and inlets around the Keys.

Russell was far from being the only rumrunner in the Keys during the Prohibition era. After all, it was the Depression. Times were hard in Key West, and good liquor sold for forty dollars a case up north. It wasn’t legal by any means, but a man had to feed his family. More than one islander, who could drive a boat made the trip from Key West to Havana on a regular basis, bringing back nothing but the best in whiskey and rum.

Between rum running and operating a speakeasy, Joe did pretty well for himself during Prohibition. By the time the Volstead Act was repealed in December of 1933, he had squirreled away enough money to open a legitimate business.

Located at 428 Greene Street, the Blind Pig was a door-less run-down building that Russell leased for three dollars a week. It had sawdust on floor, pools tables, and gambling. The prevailing attitude was “come as you are and stay as long as you want,” literally, since it was open twenty-four hours a day.

It was a free-wheeling fisherman’s bar featuring ten-cent shots of gin and nickel beer. No matter what kind of scotch whiskey a customer requested, he was generally served a measure of Teacher’s, the cheapest brand around at thirty-five cents a drink. The rowdy, come-as-you-are saloon, was renamed the Silver Slipper upon the addition of a dance floor, but that didn’t matter, it remained a place of shabby discomfort, good friends, gambling, and fifteen-cent drinks.

The place might not have been fancy, but it was home to Joe Russell and his crowd for three and a half years.

That crowd included (and, in great part was centered around) Ernest Hemingway. Captivated by Key West’s rowdy atmosphere and spectacular fishing, Hemingway was the first famous author to make the island his home.

The Hemingway Connection

Hemingway arrived on a steam ship from Havana in April of 1928 with his second wife, Pauline, after a bone-chilling winter in Paris and an ocean crossing from Marseilles. He had already published “The Sun Also Rises” two years before and was working on the manuscript that would become “A Farewell to Arms”.

Most people who know their Key West history are familiar with the stories about Sloppy Joe’s, and know it was Ernest Hemingway’s favorite watering hole during his time on the island. When Joe Russell officially opened his bar, Hemingway and his “Mob” of cohorts were enthusiastic regular customers. In fact, the author once called himself a co-owner silent partner in the enterprise. The “Mob” was comprised of some of the literary lights of the day as well as a variety of famous and infamous local residents: John Dos Passos, Waldo Pierce, J.B. Sullivan, Hamilton Adams, Captain Eddie Saunders, and Henry Strater. They wrangled, drank, and philosophized the days and nights away, never knowing they were building a legend.

When Hemingway first arrived in Key West and tried to cash a royalty check at the local bank on Front Street, the bank manager refused to cash the check. He did not think a man wearing shorts and flip flops would be in possession of the check. Hemingway went over to Russell’s place where Joe cashed that check, and all his future checks. The two men became good friends and over the years they fished the Gulf Stream between Key West and Cuba.

Hemingway called Russell “Josie Grunts” and used him as the model for Freddy the owner of Freddy’s bar and captain of the Queen Conch in the novel “To Have and Have Not” – and in many ways for the books protagonist Harry Morgan.

It was Hemingway who encouraged the bar’s final name change to Sloppy Joe’s Bar. The new moniker was adopted from Jose Garcia Havana club selling liquor and iced seafood. Because the floor was always wet with melted ice, his patrons taunted this Spanish Joe with running a “sloppy” place… and the name stuck. Somehow, it seemed to fit Joe Russell’s bar just as well.

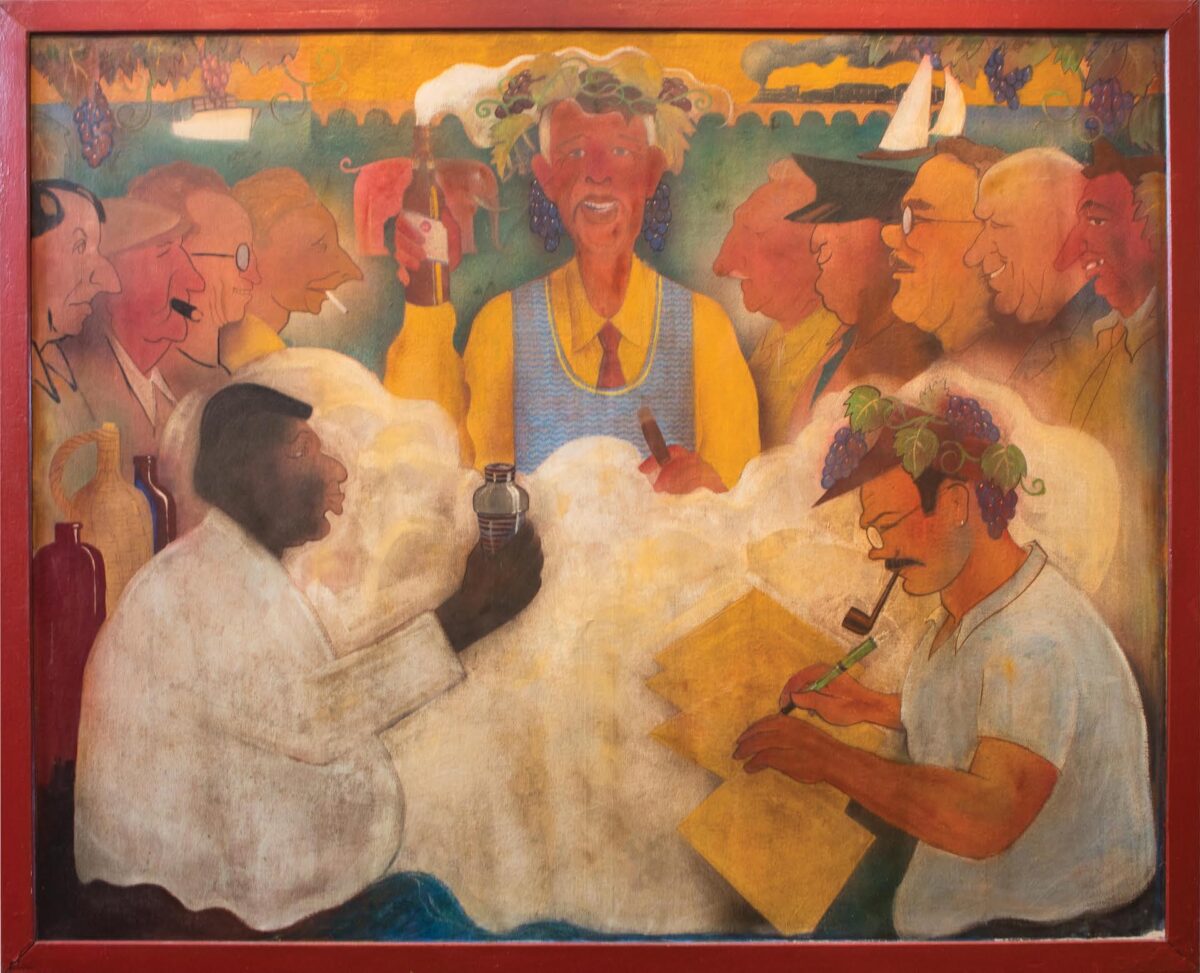

In those days, Hemingway was not the only inhabitant of Sloppy Joe’s Bar who could be called larger than life: there was also “Big” Skinner, the hearty bartender who tipped the scales at 300 pounds and served customers for more than two decades. Skinner presided over a long, rakishly curving bar and was captured as one of the characters in “Hemingway and Friends” painted by WPA artist Erik Smith.

The WPA, in fact, attempted to revitalize Key West’s failing economy during the depths of the Depression. However, Hemingway ultimately had a far greater impact on its recovery by vividly portraying the island’s Depression desperation in his brilliant “To Have and Have Not” published in 1937.

Library of Congress Arthur Rothstein 1938

And then Sloppy Joe’s disappeared

1937 was a pivotal year for Joe Russell. He and his landlord, Isaac Wolkowsky, had a heated dispute when Wolkowsky raised the rent on the bar from three dollars a week to a whopping four dollars a week. Joe was so incensed that he decided to move, but a clause in his lease prohibited him from removing any of the furnishings and other accoutrements in the bar.

Joe Russell was not going to let a little thing like that stop him. Before long, the determined saloon-keeper had solidified his strategy.

Luckily, the former Victoria Restaurant owned by Spanish emigrant, Juan Farto, was vacant. Located at the corner of Duval and Greene Streets, the Victoria Restaurant had been built in 1917 and incorporated beautiful Cuban tilework, busily whirring ceiling fans, and jalousie doors. Joe Russell quietly paid Farto $2,500 for the building.

Shortly after his dispute with Russell, Isaac Wolkowsky took off on a business trip. Joe’s lease expired while the landlord was away; and it was then, on May 5, 1937, that Sloppy Joe’s Bar disappeared.

Victoria Restaurant 1920s

Florida Keys Public Library collection

Of course, it did not actually vanish. It just relocated very fast when Joe, figuring he was no longer bound by the terms of the expired lease, he recruited a midnight mob of Key West drinkers to help him. Together, they carted every scrap of Sloppy Joe’s Bar (except the walls of the building) down the block and across to the new quarters at 201 Duval Street.

In true Key West fashion, the bar never actually closed during its fast-paced migration. Customers simply picked up their drinks and carried them away along with everything else. Service resumed with barely a blink and liquid refreshments were on the house – the new house – for the rest of the night.

Wolkowsky was predictably furious when he returned and found he was no longer Joe Russell’s landlord, but there was nothing he could do about it. When Hemingway, who had been in Spain at the time, was informed of the saloon’s unceremonious relocation, his response was simple and to the point “only in Key West.”

Sloppy Joe’s Bar’s address may have changed and its square footage nearly doubled, but its atmosphere remained the same. It boasted the longest bar in town, a walled-off room often used for gambling, and adorning one wall was a 119-pound sailfish caught by Hemingway.

Years after Sloppy Joe’s Bar’s moving night, the writer relocated as well, although not quite as abruptly as the watering hole had. Hemingway had met Martha Gellhorn, who was to become his third wife, at Sloppy Joe’s. By December of 1939, he and Pauline were separated and he had established a new home in Cuba.

When Hemingway left Key West for good, he left behind many of his personal possessions and papers, which were packed up by his long-time friend Toby Bruce and ultimately moved into a back room at Sloppy Joe’s. The back room was call “the Hole” (a back room behind the long horseshoe-shaped bar) and this time capsule was not opened until after his death more than twenty years later.

The back room remained untouched until 1962, a year after Hemingway’s death, when his fourth wife Mary opened the room and took possession of them. Uncashed royalty checks, guns, hunting trophies, photographs, and original manuscripts, including sections of “To have and Have Not” were among the items found. Mary Hemingway allowed Sloppy Joe’s Bar’s owner, who was at the time, Stan Smith, to keep some of the memorabilia for display in the bar.

In June of 1941, Joe Russell died suddenly by either of a stroke or heart attack while visiting the Hemingway in Havana.

The Tradition Continues

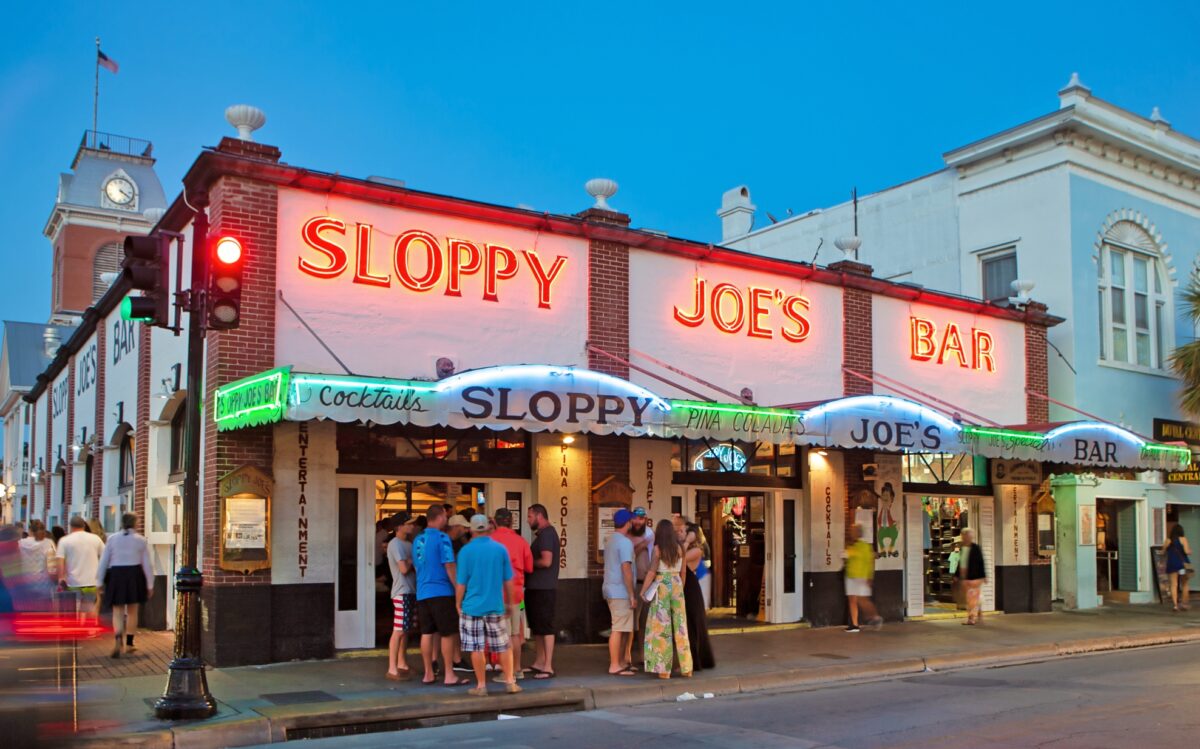

Over the years, Sloppy Joe’s Bar, like a rare Cuban rum, has gained a richness and flavor while retaining its unique atmosphere. The ceiling fans still whisper purposefully, the jalousie doors still open on the intersection of Duval and Greene Streets, busier now than ever Hemingway could imagine, yet still colored by the off-beat ambiance that prompted him to brand the island “the St. Tropez of the poor.” The long curving bar wears the scars left by generations of visitors and Hemingway aficionados, drawn by the writer’s legend and hoping some measure of magic will rub off on them.

Since its beginnings under the able auspices of Josie Russell, Sloppy Joe’s Bar has had a number of owners. Among them are Joe Russell, Joe Russell, Jr., and Stan and Marcy Smith. Since, 1978, the historic watering hole has been owned by Sloppy Joe’s Enterprises comprised of families of the late Sid Snelgrove and the late Jim Mayer.

Just as in Joe Russell’s day, Sloppy Joe’s bartenders’ welcome patrons at virtually all hours of the day or night. The satisfyingly large drinks and casual, undemanding atmosphere so successful in Russell’s reign remains, as does the sense, strong as a pulse beat, that something exciting is always about to happen at Sloppy Joe’s Bar.